Mechanisms of Adaptive Thermogenesis in Severe Restriction

Published: February 2026

Introduction

Adaptive thermogenesis represents one of the most significant physiological responses to severe caloric restriction. This process encompasses the reduction in metabolic rate below what would be predicted based on body weight alone, reflecting the body's adaptive response to perceived energy scarcity. Understanding the mechanisms underlying this response provides important context for how physiological systems respond to extreme dietary restriction.

Definition and Overview

Thermogenesis refers to heat production and energy expenditure within the body. Adaptive thermogenesis specifically describes the physiological downregulation of energy expenditure that occurs during caloric restriction. This represents an adjustment of the metabolic machinery rather than a permanent alteration, though the duration and magnitude of adjustment varies between individuals.

Hormonal Signalling in Metabolic Adaptation

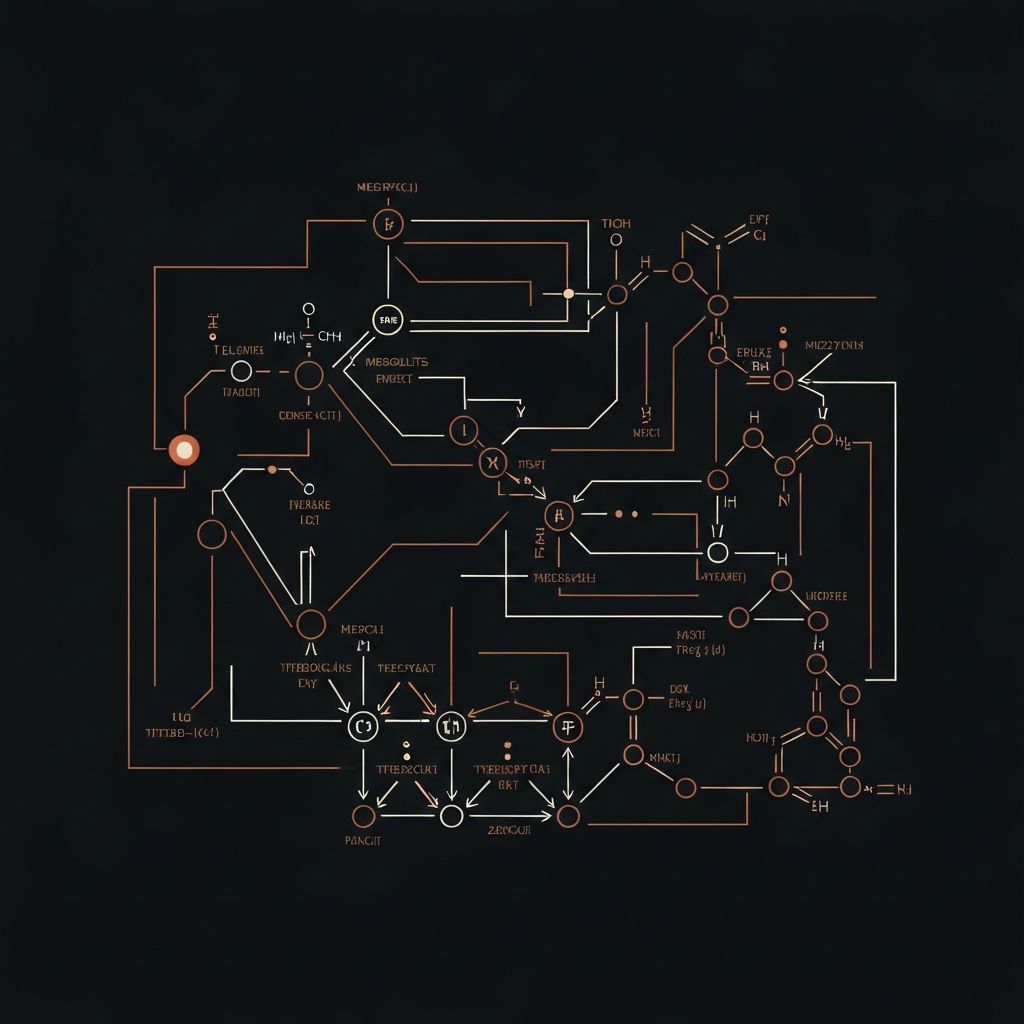

Multiple hormonal systems coordinate the metabolic adaptation response to energy deficit. Thyroid hormones, particularly T3 (triiodothyronine), decrease during severe restriction. Since thyroid hormones act as metabolic "accelerators," stimulating energy expenditure and protein synthesis, their reduction directly reduces metabolic rate. This change occurs relatively rapidly, within days of beginning restriction, and represents a primary mechanism of metabolic downregulation.

Leptin, the energy status hormone, decreases proportionally to energy deficit. Beyond its appetite-regulating functions, leptin acts on the hypothalamus to stimulate metabolic rate and thermogenesis. Leptin reduction therefore contributes to decreased metabolic rate independent of appetite signalling changes. The magnitude of leptin decrease depends on both the degree of energy deficit and changes in body fat stores.

Sympathetic Nervous System Changes

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS), part of the autonomic nervous system regulating unconscious bodily functions, shows reduced activity during severe restriction. SNS activity normally stimulates thermogenesis and increases metabolic rate through norepinephrine release acting on beta-adrenergic receptors. During restriction, reduced SNS tone contributes to decreased energy expenditure.

This reduction in sympathetic activity appears to be mediated by leptin signalling—lower leptin levels signal the brain to reduce sympathetic activity as a conservation mechanism. The interaction between leptin and sympathetic function represents an integrated physiological response to energy shortage.

Mitochondrial Adaptation

At the cellular level, mitochondria—the "powerhouses" of cells responsible for energy production—demonstrate altered efficiency during severe restriction. Uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) and similar uncoupling proteins are involved in thermogenesis by allowing energy to be released as heat rather than captured in the chemical bonds of ATP (adenosine triphosphate). During restriction, the expression and activity of these uncoupling proteins decrease, resulting in more efficient energy capture with less heat production.

This mitochondrial adaptation represents an energy conservation strategy at the cellular level, paralleling the systemic metabolic downregulation occurring at the organismal level. The mechanisms appear coordinated through hormonal and neural signalling cascades.

Activity Energy Expenditure Reduction

Metabolic rate reduction during restriction includes decreased energy expended in physical activity and non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT—the energy expended during daily movement and postural maintenance). Individuals often unconsciously reduce movement frequency and intensity during severe restriction. This reduction reflects both adaptive physiological mechanisms reducing spontaneous activity and behavioural changes reducing conscious physical exertion.

NEAT represents a substantial portion of daily energy expenditure in many individuals, often comprising 15-30% of total daily expenditure. Reductions in NEAT during restriction can therefore significantly reduce overall metabolic rate.

Protein Metabolism Changes

Severe restriction reduces protein turnover (the continuous breakdown and synthesis of body proteins) and decreases the thermic effect of food—the energy required to digest, absorb, and process nutrients. Since protein metabolism is metabolically expensive compared to fat or carbohydrate metabolism, reductions in protein turnover reduce overall metabolic rate. This adaptation helps preserve energy but also contributes to lean tissue loss during prolonged restriction.

Duration and Magnitude of Adaptation

Metabolic adaptation follows relatively predictable patterns based on deficit magnitude. Very severe restriction (below 800 kcal/day) typically produces more rapid and pronounced metabolic adaptation compared to moderate restriction. The metabolic rate reduction may range from 5-25% below predicted values depending on restriction severity and individual characteristics.

Importantly, metabolic adaptation is not unlimited. Even with extremely severe restriction, metabolic rate does not drop to zero or remain indefinitely at depressed levels. Research suggests metabolic rate floors exist, below which further restriction does not produce additional downregulation.

Individual Variation in Adaptation Response

Considerable individual variation exists in both the speed and magnitude of metabolic adaptation. Some individuals show rapid adaptation within days, whilst others demonstrate slower adaptation over weeks. Genetic factors appear to influence adaptation speed, as do age, sex, baseline metabolic state, and prior dieting history. This variation means that population averages do not accurately predict any individual's specific adaptation response.

Recovery After Restriction

When caloric restriction ends and normal eating resumes, metabolic adaptation demonstrates incomplete and variable recovery patterns. Metabolic rate typically increases relatively quickly (within days to weeks) as energy availability increases. However, complete metabolic rate recovery to pre-restriction levels may take weeks to months, and some individuals show persisting metabolic suppression even after returning to normal energy intake.

The lag in metabolic recovery, even when food intake returns to maintenance levels, represents a factor in weight regain patterns—the body is expending fewer calories than pre-restriction despite similar food intake, creating a temporary energy surplus.

Clinical and Research Context

Understanding metabolic adaptation provides important context for interpreting weight loss plateaus during restriction and weight regain after restriction. The adaptive responses are normal physiological mechanisms, not evidence of metabolic "damage" or permanent alteration. However, they do represent significant factors influencing both the trajectory of weight loss during restriction and the challenges in maintaining weight loss after restriction ends.

Educational Information: This article explains physiological mechanisms observed in research contexts. It does not constitute medical advice or personal recommendations. Individual responses to dietary practices vary considerably. For health-related decisions, consult qualified healthcare professionals.